Links to the Missing:

Exploring How Technology

Is Used In Locating Missing Persons

Links to the Missing:

Exploring How Technology

Is Used In Locating Missing Persons

A Learning

Module

developed by Mrs. Cirino

for our 4th Grade Classroom

The purpose of this learning module is for you to learn about the importance of being safe. We are going to investigate the information required to identify missing persons and create personal databases with information about ourselves and our community. We are going to be able to outline maps, that would assist someone by identifying the routes you normally take and places you frequently visit.

We are going to be able to read articles that will teach us how technology is being used in locating missing persons.

At the end of our module, we have the wonderful opportunity to interview two people who are directly connected to safety in their careers. One person is Mr. Moller, who is a police officer with the Union City Police Department. The other person is Mrs. Haney, who is a public dispatcher with the San Jose Police Department. Both of these professions have agreed to take time from their busy schedules to allow us to interview them on safety procedures. We can ask them questions on how we can all be safe. The best part is that after we gather all of our information, we can design a website that will enable us to share what we have learned with other students. This website can help children to learn ways in which they can be safe, too.

![]() Think

Sheet #1

Think

Sheet #1

Look carefully at your partner, and make a list of distinguishing characteristics that would help identify this person. What would you need to know about this person if you were asked to give a detailed description of what he or she looks like?

(Most of us have already completed this section and have already drawn portraits of our partner. If you still have to finish your list or portrait, please do this before going to Think Sheet #2.)

![]() Think

Sheet #2

Think

Sheet #2

Take turns interviewing each other to learn about where your partner goes after school. What route do they travel to get to that location? What are some of the key places they pass on their way to their after school location? If this person was missing, what information could be given to investigators to help them locate this person?

![]() Think

Sheet #3

Think

Sheet #3

Make notes so that you will be able to share your answers with the class. Your oral presentation should be no more than five minutes. Remember to use our classroom oral presentation rubric.

![]() Think

Sheet #4

Think

Sheet #4

Please think about what you know about how technology has assisted in helping to locate missing persons. Write down some thoughts and discuss these with your collaborative group.

![]() Think

Sheet #5

Think

Sheet #5

Read and discuss the New York Times article, “Nightmares’ End, With Technology’s Aid,” focusing on the following questions:

§ Why did the woman in the trailer park go to the web site missingkids.com?

§ Why was Jonathan Kenderes listed on this site?

§ What did she do after she discovered Jonathan on the site?

§ According to the article, what indisputable advantage has technology afforded?

§ What percentage of kidnapped children and runaways were recovered in 1989? What is the recovery rate now?

§ According to Ernie Allen of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, in what three ways has technology made a difference in missing children cases?

§ According to the article, how are forensic artists using technology to construct photos of missing children?

§ How does a “fax dissemination service” such as ChoicePoint help in missing children cases?

§ What is included in the ChoicePoint database? How successful is the use of such a database, according to the article?

§ How as the web site run by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Persons useful in recovering a child from an abductor in Puerto Rico?

![]() Think

Sheet #6

Think

Sheet #6

We will be creating a personal database that might be given to a dissemination service such as ChoicePoint. This database will include a personal description, as well as detailed information about your primary locations and a map of your local community, following these guidelines:

![]() Personal Description

Personal Description

· Write a clear description of yourself that would help investigators to identify you. Include the following:

o Your full name

o Your date of birth

o Hair color and type

o Eye color

o Nationality or ethnic background

o Height and weight

o Distinguishing features

o Favorite clothes

o Favorite foods and entertainment

o Personal likes and dislikes

![]() Community Description

Community Description

· Create a detailed description of your local community that would help investigators locate the places where you are likely to go. Look up specific addresses for the following:

o Where is your school located?

o Where are you likely to go after school?

o Who are your closest friends?

o What are your favorite places to visit on weekends?

o What are the stores that you frequent most?

o What is your local police precinct?

o Where are the emergency medical facilities in your community?

![]() Community

Map

Community

Map

· Create a map that includes the places that you identified in your community. Go to Mapquest (http://www.mapquest.com/main.adp) or another map site, and print out the maps and aerial photographs that show these places. Use the “Add a Location” feature to add icons that mark key locations and create a legend that identifies the icons on your map.

Work

with the members of our classroom Technology Club.

They will help you set-up your database!

Have all of your information organized on paper,

before going to the computers.

![]() Think

Sheet #7

Think

Sheet #7

After you have finished gathering all of the information and it is entered into your personal database on the computer, you will publish your personal database in a booklet.

Work with the members of the Technology Club to print out your information in an organized format. Make a report in a booklet format. Be creative!

![]() Think

Sheet #8

Think

Sheet #8

As a class, we will discuss the experience we have had so far with this learning module.

Then, in your collaborative groups, discuss the following questions:

![]() Think

Sheet #9

Think

Sheet #9

Visit MissingKids.com (http://www.missingkids.com/) and review the pages listed under “How I Can Help”.

Pick one of the suggestions listed and write a description of how you could help locate missing children in your community.

What specific steps would you need to take to implement one of these campaigns?

Please be ready to share your ideas with your group and then with the class.

Our Final Activity:

We have the opportunity to interview two people who are professionals in the field of safety. One person is a public dispatch officer and the other is a police officer. Let's prepare wonderful questions in advance, so that we can gathering all of the information we need to make a great safety plan for all children to benefit from!

In your groups, write and discuss the questions we want to ask each person. Investigate by searching the Internet and know what a public dispatch officer and a police officer does and how their positions relate to safety.

After the interview, please use the information contained in our Student of the Week Activities, to write a friendly letter to Mrs. Haney and Mr. Moller, thanking them for taking their time to visit us and how the interview will assist us in preparing our safety plan.

Now, let's gather all of our data and begin formatting a Power Point Summary Presentation of our safety plan. We will then publish this information on our classroom website!

As a class, we will write a more detailed report on our safety plan and link the document to the website!

CONGRATULATIONS!

We just completed our first

Language Arts Learning Module!

Great Job!

For

any students at home with far too much time on your hands:

For

any students at home with far too much time on your hands:

Challenge Activities:

1. According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, in the vast majority (nearly 95 percent) of kidnap cases, a family member is the kidnapper. What do you think accounts for such a high number of family abductions?

2. The NCMA also reports that the majority of missing children are runaway cases. Why would a teenager want to run away from home? What are some ways you can help someone who is at risk of leaving their home?

3. The U.S. Department of Justice (http://www.ncjrs.org/html/ojjdp/2000_04-4/contents.html) distinguishes between “missing”, “abducted”, “runaway”, and “thrown away” children. What are the differences between these categories?

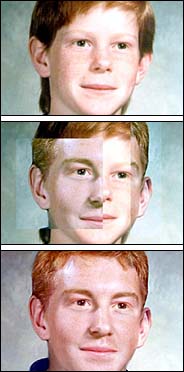

PASSED TIME - Images of long-missing children are created by merging old photos with those of relatives or others. Mark Himebaugh was kidnapped at age 10 in 1980.

![]() STRANGE.

The two boys had been in the trailer park for a week. It was April, but it wasn't

spring break. Why weren't they in school?

STRANGE.

The two boys had been in the trailer park for a week. It was April, but it wasn't

spring break. Why weren't they in school?

A woman living in the trailer park, in Morgan Hill, Calif., thought there was something suspicious about the boys and the man who had brought them there. She befriended the younger boy, a sullen 4-year-old with brown hair who was prone to temper tantrums. But she could extract only his first name: Jonathan.

On impulse, she went on the Internet and found a Web site, www.missingkids.com. She clicked on Search for Child Photos and typed in Jonathan. A page of missing Jonathans appeared — a toddler with a clip-on bow tie; a darkly handsome teenager; the boy from the trailer park, dressed in a tomato-red turtleneck with a glint in his eye.

That glint had dulled. Jonathan Kenderes and his brother, Andrew, had been taken nine months earlier, in July 2000, by their father, who had lost custody of his sons during a divorce. They had moved from trailer park to trailer park, never staying more than a few days.

The woman, who has asked to remain anonymous, called the police. That night, the father was arrested for kidnapping and custodial interference. The mother, Elizabeth Norton, flew out from New York the next morning.

"With technology, they were brought home," Ms. Norton said. "Without it, who knows where they would be now?"

Economists debate whether technology has increased productivity. Sociologists argue whether instant communication has improved or damaged the quality of life. But technology has had a quantifiable impact in at least one area: it is helping to bring home thousands of missing children.

The recovery rates for the most serious missing-children cases have jumped sharply in the last decade, an increase that experts attribute mostly to advances in computer and communication technology.

In 1989, about 62 percent of kidnapped children and runaways whose safety was considered seriously threatened were recovered safely, according to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a nationwide clearinghouse, which handles 6,000 to 7,000 such cases a year. Now the recovery rate is about 93 percent. (The rate for all cases reported to the police, which includes those in which the child was merely separated from a parent for several hours, is more than 99 percent.)

The improvement is even greater among the 5 percent of cases in which the kidnapper is not a family member. Before 1990, the recovery rate for such cases was about 35 percent. Since then, the recovery rate has been about 90 percent, the center reported.

"Technology has made a difference at every juncture," said Ernie Allen, the chief executive of the center, a private agency that was started in 1984 and is financed by the Department of Justice and private contributions.

"It has helped us to get information out to the public," Mr. Allen said. "It has enabled us to capture lead information. And it has enabled us to analyze that lead information and get it to law enforcement."

In other words, it helps to have magnets when looking through a haystack. Today, the magnets come in many forms, including e-mail messages, faxes, databases and Web sites (the center operates www .missingkids.com).

But technology helps in less obvious ways as well. Adobe Photoshop, for example, plays an important role in letting forensic artists more quickly and easily create an age-progressed photo — an image of what a child who has been missing for years would look like today.

"Before Photoshop, they used to render the images pixel by pixel overnight," said Joe Mullins, a forensic artist at the center. "Now with functions like Liquefy, you can stretch an entire face instantaneously."

For most cases, speed is often of the essence. The longer a child is missing, the less likely the child will be recovered safely. A study in 1997 by the Department of Justice found that 74 percent of children who were kidnapped and murdered were killed within three hours of their abduction.

Ten years ago, photos of missing children had to be sent by overnight mail to the center's headquarters outside Washington. The center would have posters printed, a process that could take a week. The posters then had to be distributed by mail to areas outside the immediate vicinity of the child's disappearance.

"So effectively it might be 10 days, 2 weeks, 3 weeks before we were able to widely disseminate the photos of the missing child," said Mr. Allen, who has been with the center since its creation.

Today, a poster can be created within 30 minutes of an abduction. A photo of a missing child can be scanned and e-mailed within minutes of an initial report. The center can then make electronic posters within five minutes. E-mail alerts are sent to law enforcement agencies and volunteers to tell them to download the posters. The center also sends mass faxes using ChoicePoint, a company that provides fax dissemination services.

Searching is a numbers game — the more information is disseminated, the better the chances of recovery. So saturation, as well as speed, is important.

The center has a database of 3.8 million businesses and agencies nationwide, including dentists' offices, highway rest stops and Wal-Mart stores, for its fax operation. The center blankets the geographic area where the child disappeared in the hope that somewhere, someone will recognize the child or abductor in the photo. Surprisingly, often somebody does. About one in six recovered children is located as a result of someone in the general public recognizing a photograph.

On Nov. 2, 2001, a nurse at the Harris County Health Clinic in Baytown, Tex., saw an adult come in with an infant to request treatment. The nurse recognized the abductor from a fax alert; the infant had been taken a month earlier by a friend of the mother. The nurse called the police and the abductor was arrested.

Technology has been effective in pushing photos out to the public; it has also made it easier for the public to go to the photos.

The site run by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children has more than 2,500 photos and profiles of missing children from around the world. Supported by Sun Microsystems, Computer Associates and other companies, it has played a role in the recovery of hundreds of children. Runaways, who account for about 75 percent of missing-children cases covered by the center, often see their photos and return home.

In other cases, the Web site has seemingly pushed the stars into alignment. In 1998, a police investigator in Puerto Rico had suspicions about a 7-year-old girl who had been removed from her home because of suspected child abuse. He logged on to the missing-children site and painstakingly scrolled through hundreds of photographs. But he kept coming back to a photo of a baby because of a purplish birthmark above her mouth.

The toddler was Crystal Anzaldi, who was abducted in 1990 from her home in San Diego while her parents were sleeping. She had been taken to Puerto Rico by her abductor.

"Before technology, before the Internet, before connectivity, that child was unrecoverable," Mr. Allen said. "That officer in San Juan would have no way to determine that is a missing child."

Even years after a child disappears, technology can help keep a case alive. Mr. Mullins and other forensic artists work in a corner on the second floor of the center's headquarters.

To create age-progressed images, they electronically manipulate a photo of the long-missing child and combine it with a photo of an older relative or one from a library of 23,000 anonymous portraits donated by school photography companies.

A decade ago, the age-progressed pictures could take days to create. Today, with Adobe Photoshop, the artists can turn out an age-progressed image in about four hours. On the monitor screens, the faces stretch and melt into each other like colorful digital putty.

To date, 320 children have been recovered using age-progressed photos. Often it is a small feature in the photo that jogs a viewer's memory. "It's amazing how people pick up on the little facial details," Mr. Mullins said. "The shape of the nose, or the corner of the mouth."

A sadder role for the forensic artists is to recreate the face of a dead child, using morgue photos or skulls that have been recovered.

Last year, after a teenage boy's remains were discovered in the Nevada desert, his head pierced by a bullet, an artist used the skull to construct a facial image. A man whose son had run away years ago called the center after he saw the image on television. DNA tests proved it was indeed his son.

While technology had not brought the boy back alive, it did provide some comfort to the father.

"He was able to bury his son and get on with his life," Mr. Allen said.

![]() Return to Mrs. Cirino's Classroom Homepage

Return to Mrs. Cirino's Classroom Homepage